Sustainable Investing History

Table of Contents

When The John Merck Fund embarked on a 10-year spendout of its assets in 2012, we aimed to maximize our grantmaking clout across four core program areas. Yet we also set ourselves another challenge: to finance the effort as much as possible with sustainable investments consistent with our philanthropic mission—and, what’s more, to do this without sacrificing market-rate returns.

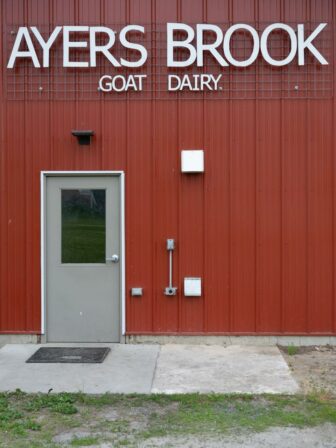

JMF Sustainable Investment Percentages, 2011–2021

(Prime Buchholz LLC)

By shifting to “sustainable” holdings across the portfolio, we hoped our investment choices would reflect our grantmaking objectives—or at least not contradict them, as might be the case, for instance, if we held oil investments while making clean-energy grants. But because we planned to pay out a total of $94 million in grants and administrative expenses during the decadelong spendout, we needed healthy returns from a portfolio that at the start of the period was valued at $75.9 million. Further, the first eight years would require particularly strong performance, because the Fund’s portfolio would have to be transitioned subsequently to lower-risk, lower-return assets to ensure liquidity in the spendout’s final years.

The strategy, in short, reflected a belief that good sustainable-investment managers could deliver financial returns equal to or better than those of traditional managers. This confidence was well placed, as we exceeded our target by a wide margin. Over the 10 years, we paid out $103.5 million—$91.5 million in grants and $12 million in administrative expenses—on the strength of a portfolio weighted heavily toward investments deemed sustainable based on environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) considerations. Representing 12% of our holdings in 2011, sustainable investments grew to 90% at their high point in 2018, permeating all asset classes in the Fund’s diversified portfolio.

The results helped support a then-nascent view in the investing world that socially responsible financial management need not come at the expense of market-rate returns. They also demonstrated that investing with societal impact in mind could succeed in the arguably more complicated context of a foundation spendout.

While engaged in this effort, we publicly advocated for sustainable investing and associated ourselves with other organizations and institutions embracing the practice. For example in 2014, we became an early signatory of the Divest-Invest campaign, a global network of organizations committed to divesting from fossil fuels and investing in climate solutions. We also took early positions in funds that pioneered sustainable-investing products, and we hired advisors developing expertise in this field.

There were, to be sure, hurdles along the way. For instance, the social, environmental, and governance impacts of prospective investments—and their alignment with our mission—sometimes proved difficult to parse. Nor could the entire portfolio be shifted to sustainable investing overnight, given that some asset classes initially lacked mission-aligned products with a track record of returns at or above market rate. Further complicating matters was the fact that we had to avoid illiquid investments with terms longer than the 10 remaining years of the Fund’s life. That consideration often meant steering clear of private equity, even though this asset class can offer far better opportunities for targeted program impact than public equity.

In addition, there were paths not taken. One of these would have been to do away with grantmaking altogether and to instead pursue our goals through sustainable investing alone. Nevertheless, when we closed our doors in 2022, we took pride in having used portfolio investing to magnify our mission impact. Equally important, we felt we had played a part in nurturing the sustainable-investing movement in its critical early years.

“It is important to recognize how most foundations and much of the investment world viewed sustainable investing in 2010–2011,” Rick Burnes, founder of the venture capital firm Charles River Ventures and a member of The John Merck Fund Investment Committee, said in 2022 as JMF prepared to close its doors. “The conventional wisdom was that applying a sustainable investing criterion would seriously reduce performance—that you would be fighting with one hand tied behind your back. Since then, there has been a shift, with many in the foundation and business-investment communities recognizing the importance of the ESG movement and that investment performance can be maintained. The John Merck Fund was very much a part of that movement.”

Early steps

The Fund was not new to sustainable investing when we launched our spendout in 2012. Beginning decades earlier, we had divested the Fund of tobacco and firearms holdings, reviewed the impacts of other companies in our portfolio, and engaged in shareholder advocacy. And starting in the early 2000s, we made several mission-aligned investments. These ranged from a pair of Vermont loan funds—one targeting community development, the other local agriculture—to a global equity fund, Generation Investment Management, with stakes in companies deemed compatible, in its words, with a “low-carbon, prosperous, equitable, healthy, and safe society.”

These early steps, though, did not lead quickly to a full embrace of sustainable investing, which a number of trustees worried would depress returns and thus shrink the grants budget. As late as October 2010, sustainable investments only accounted for 5.5% of the Fund’s portfolio. Still, sustainable-investing champions among the trustees and staff persisted through these years, organizing periodic board meetings with experts in the field, and raising the portfolio-alignment question during Fund retreats. This ongoing engagement ultimately helped turn the tide, as did generational change in the Fund’s leadership and growing advocacy for sustainable investing in the wider world.

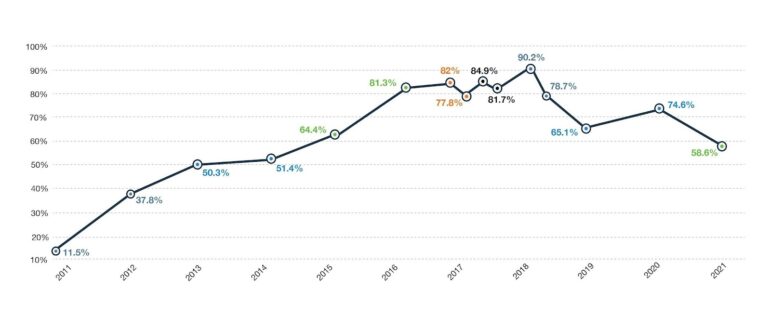

JMF Annual Payout Percentage, 1980–2021

(Prime Buchholz LLC)

*Payout is the total of grants plus all program-related expenses.

Deepening concern about global warming in many ways served as a catalyst, with climate-protection advocates increasingly calling on institutions to rid their portfolios of carbon holdings. Among these advocates was environmentalist and author Bill McKibben, who in a widely shared 2012 article in Rolling Stone, urged college students to demand their schools take action in this arena. “If their college’s endowment portfolio has fossil-fuel stock, then their educations are being subsidized by investments that guarantee they won’t have much of a planet on which to make use of their degree,” McKibben wrote.

(Creative Commons/Dave Brenner)

At the same time, rigorous retrospective analysis made possible by advances in digital technology suggested that exclusion of carbon from investment holdings, though challenging for practical reasons in the case of commingled funds, presented minimal overall portfolio risk. The view gained traction among respected investors, some of whom acknowledged that carbon holdings themselves would become increasingly risky over time.

“[T]he request put forward by Bill McKibben and others is very doable,” Tom Steyer, a hedge fund manager and 2020 U.S. presidential candidate, told students and faculty of Middlebury College in 2012. “It asks you to make a statement of principle now, [to] stop investing new money in this area, and then [to] spend a number of years winding down positions. … The available research, looking backward, shows that the return penalty would be tiny; but in any event, good investors rarely look backward. Looking to the future, the data on climate change makes it clear that something has changed. And as the rest of the world realizes this, fossil-fuel stocks will come under increasing pressure.”

Custom approach

The work to draft a sustainable investing strategy began in earnest in 2011, when our board decided to spend out virtually all of the Fund’s remaining resources during the period 2012–2021 and to close its doors definitively in 2022. A board subcommittee recommended that the Fund shift as much of its portfolio as possible to sustainable holdings, using market-rate investments across all asset classes and, when feasible, narrowly focused program-related investments (PRIs).

At the same time, though, we would maintain portfolio diversification by hewing to existing asset-allocation guidelines. The subcommittee proposed that the new approach be embedded in our investment policy, the overarching objectives being to avoid holdings in enterprises that harm the environment and to embrace those that intentionally seek climate solutions.

Later in 2011 we hired two advisors to help us in this work. Imprint Capital, a firm focused on sustainable investing, was engaged in the short term to help plan the process. Prime Buchholz, a traditional investment consultant just then developing in-house sustainable investing capabilities, would collaborate with the Fund on an ongoing basis to execute the strategy throughout the spendout. With input from both firms, we ultimately approved an investment policy calling for a mission-aligned portfolio capable of supporting a total spendout originally projected to be $94 million over 10 years. Grantmaking would focus on four core program areas selected for the spendout: climate and energy, developmental disabilities, farm and food systems, and health and environment.

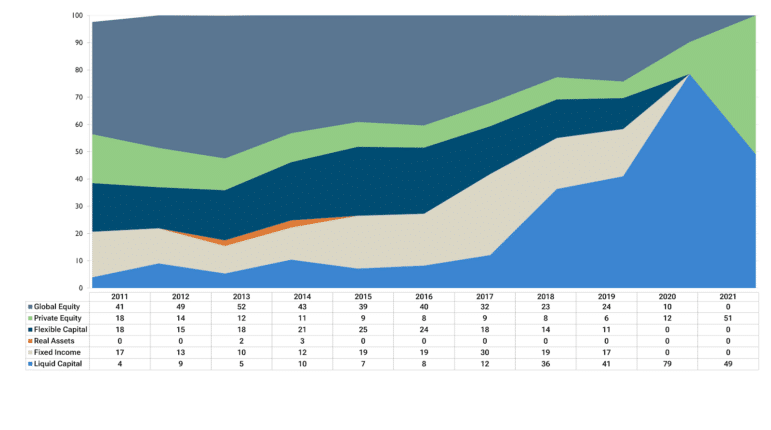

JMF Historical Asset Allocation

(Prime Buchholz LLC)

The relatively short time horizon and the grantmaking objective—an ambitious one, given the portfolio’s $75.9 million value at the outset—inevitably influenced our investment blueprint. While the new policy sought mission-friendly holdings, for instance, our board was reluctant to wade deeply into venture capital and private equity funds. That’s because these vehicles—though they are popular among mission investors—typically involved long-term commitments that exceeded the duration of our spendout. And although our grantmaking targets required strong portfolio performance and, thus, substantial equity exposure, the plan stipulated that after a certain period this exposure must be ratcheted down to dampen risk and volatility in the spendout’s homestretch.

On the advice of Prime Buchholz, we adopted a four-stage asset-allocation plan that began with a strong emphasis on growth investments in the first three years, then gradually shifted in subsequent stages to virtually 100% liquid holdings in the final three years.

“The process that freed the foundation to go forward with a robust impact-investing program relied on the rigor and care of good governance,” explained John Goldstein, who advised the Fund on behalf of Imprint Capital, in 2021. “We crafted an investment policy statement that made everyone comfortable. It insisted on staying within the guardrails of an asset-allocation strategy and a targeted rate of return, while preferencing impact investments over traditional investments where these other criteria were met. With that in hand, the organization’s goals could be advanced through its investment program as well as its grantmaking.”

Noting that individual trustees’ opinions on impact investing at the time ranged from skepticism to enthusiasm, Investment Committee Chair Anne Stetson summed up the result this way: “Imprint Capital guided us as a committee to a generative policy that worked for the doubters and the zealots alike.”

Program-related investment process

One of the trickier governance questions was how to ensure that the use of program-related investments (PRIs) would not undermine the Fund’s aggressive 10-year grantmaking target. PRIs were seen as a potentially powerful means of spurring mission-aligned economic activity in specific program areas. But because PRIs often earn lower-than-market-rate returns, untrammeled use of them in one or two program areas might unfairly erode grantmaking resources for the other programs by reducing our investment earnings overall.

These anticipated earnings were not abstractions; they formed the basis of detailed, 10-year spending plans developed by the Fund’s four program work groups, each of which typically comprised a subset of trustees, and a staff member or consultant.

To address this challenge, we set a ground rule on the advice of Imprint Capital: PRIs only would be used if the budget of the Fund program requesting it were reduced over a period of years to offset anticipated underperformance. This process guided the two new PRI-style investments made during the spendout period, both of them loans proposed by the farm and food systems work group.

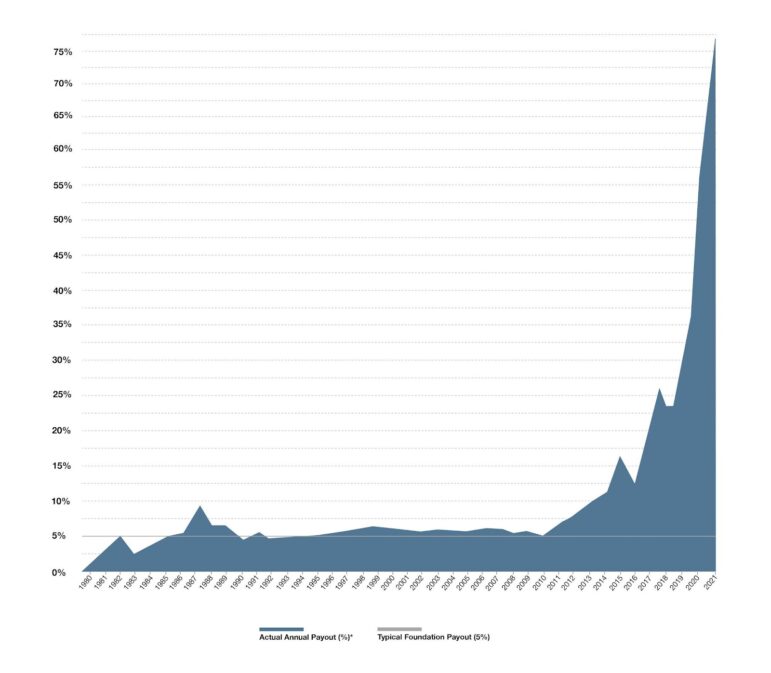

(Ayers Brook)

The John Merck Fund provided a $300,000 program-related investment for the innovative Ayers Brook Goat Dairy and a $425,000 program-related investment to provide credit support for New England food entrepreneurs. To ensure the portfolio wouldn’t suffer unduly if the loans weren’t repaid, the farm and food grantmaking budget was docked $725,000 over a period of years. But when both loans were, in fact, paid back, the funds were restored to the program’s grants budget for use during the remainder of the spendout.

The procedure ensured that project investing only occurred when the relevant program work group felt that the potential impact justified a grants-budget reduction. Effectively, the process limited the extent of PRI-style investing, but the discipline it imposed was seen as positive, even innovative.

“The integration of the program side with the investment side of things was unique,” said Alice DonnaSelva, a former consultant for Prime Buchholz who led efforts at the firm to build its sustainable investing practice and chaired its committee in charge of vetting prospective ESG investments. “In contemplating a [below-market] investment, the program side had to think whether it was willing to take a haircut. It meant that some investments didn’t happen, but that was good discipline.”

Accounting for impact

Because sustainable-investment opportunities were not initially available in some asset classes, the transition of the portfolio could not occur all at once. The key was to find investments that not only had a track record of market-rate returns, but that also advanced or reinforced—at least to some extent—the foundation’s values and goals. Although assessing potential investments from an earnings perspective was relatively straightforward, describing their “mission fit” was not.

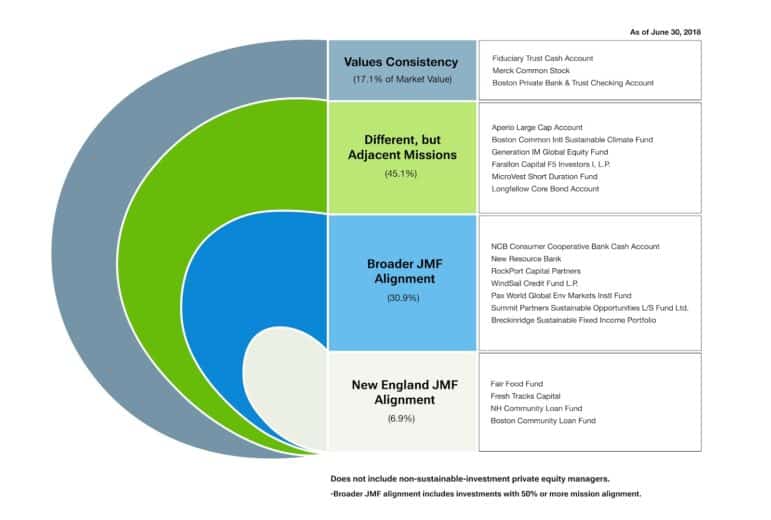

Investment Committee discussion of this challenge eventually led to the creation by Imprint Capital of a “snail chart,” a graphic showing four concentric bands, each connoting a different degree of alignment with our mission. If an investment qualified for any of the four bands, it was considered sustainable. Used regularly to update trustees on sustainable-investment progress, the chart displayed the names of holdings most closely aligned with our mission and with our prioritized New England geographical focus in the first, innermost band. Investments with the loosest alignment—yet possessing “values consistency” with the Fund’s mission—were listed in the fourth, outermost band. Ultimately, the bulk of our holdings occupied the two middle bands—the second, “broader alignment” band covering investments sharing at least 50% alignment with the Fund’s mission, and the third, for holdings that reflected different, but adjacent missions.

JMF Mission-Alignment “Snail Chart”

alignment with the Fund’s mission.

(Prime Buchholz LLC)

Importantly, we did not switch to or add sustainable investments in a given asset category until we were confident that performance expectations and genuine mission alignment could be met. In the hedge fund space, for instance, we hoped to add a second mission-friendly manager to one we already had. The new manager—Alysun, later named Summit—invested in companies focused on clean technology or environmental sustainability and shorted companies whose activities ran counter to those goals. Owing to the scant offerings of genuinely sustainable hedge fund products, however, we did not acquire another holding in that asset class until 2015, when we invested in a fund managed by Farallon Capital, a firm founded by Tom Steyer. Among the goals guiding the Farallon fund was to avoid companies linked to the fossil-fuel sector.

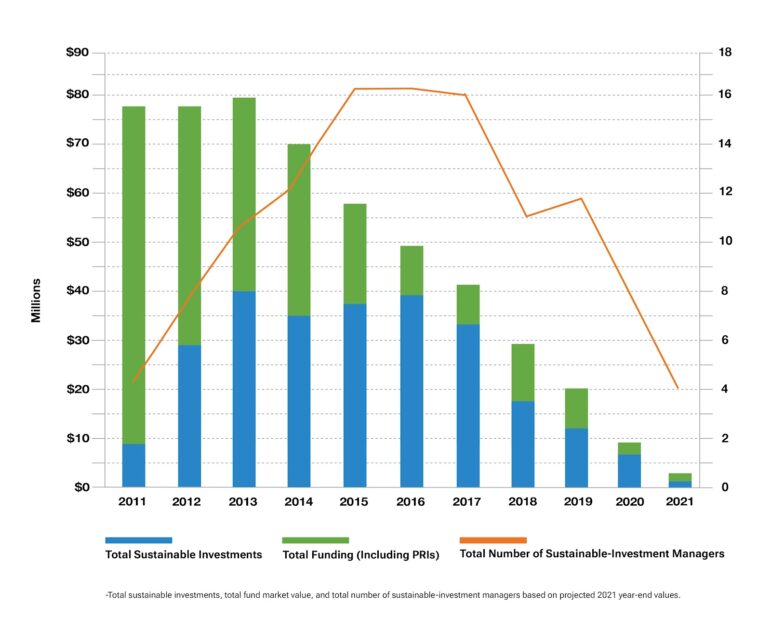

JMF Total Sustainable Investments vs. Total Fund and Sustainable Investment Managers, 2011–2021

the number of impact managers over time.

(Prime Buchholz LLC)

In other categories, sustainable alternatives were readily available. In 2012, for example, we replaced a position in the large-cap category with a separately managed account at Aperio Investments—a sustainable-investing pioneer, later acquired by BlackRock—that offered a custom-designed green-index strategy. And the next year, we replaced an existing fixed-income position with a sustainable-bond fund operated by Breckinridge, an innovative manager that targeted corporate bonds meeting ESG criteria as well as municipal bonds that delivered community and environmental benefit.

“JMF took an asset-class approach and said, ‘Which one can we impact first?’” said DonnaSelva, who after working for Prime Buchholz became a principal at the Intentional Endowments Network, a nonprofit that assists universities and other institutions in sustainable investing. “You look at what’s available and go for the low-hanging fruit first.”

Strong performance

As the deliberate investment-selection approach unfolded, the share of sustainable holdings in our portfolio grew steadily and impressively over time—from 11.6% in 2011 to 25% in 2012, 50% in 2013, and 90% by late 2018. (The total impact investment percentage declined after 2018 owing to the continued presence of legacy private equity investments that had not been liquidated by the end of the spendout. Because of the illiquid nature of private equity investments, the Fund continued to hold these positions until there was a final return of capital.)

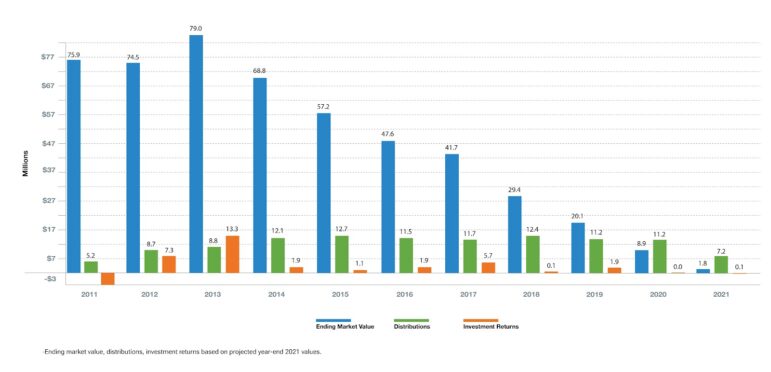

JMF Ending Market Values, Distributions, and Investment Returns, 2011–2021

as JMF drew down its funds during its spendout.

(Prime Buchholz LLC)

Crucially, the emphasis on sustainable investing did not come at the cost of portfolio performance. To the contrary, we enjoyed strong investment results during the years 2012–2021 as we spent down. Our asset allocation gradually changed to a lower-risk profile in the spendout’s latter years, a transition that inevitably dampened gains. But the years in which we had high asset values and an equity orientation were characterized by good relative performance from Generation, Summit, Farallon, and other key managers.

These managers implemented strategies that were focused on ESG and sustainability, and they did not suffer measurable performance headwinds as a result of those strategies. Generation, for example, managed to outperform its benchmark by 5% per year, all the while incorporating sustainability as a core element of its process. Similarly, Summit generated a return that exceeded its benchmark by 6% per year over the time it was in the portfolio.

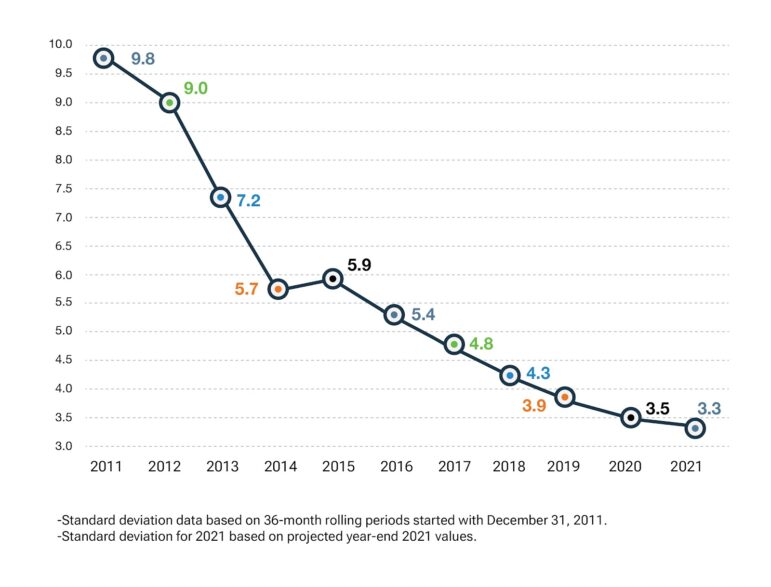

JMF Total Fund Standard Deviation, 2011–2021

(Prime Buchholz LLC)

Results such as these from ESG pioneers such as Alysun, Aperio, and Breckinridge caught the attention of the asset-management industry and its clientele, creating opportunities for other firms willing to build the expertise to incorporate sustainability into their investment criteria.

Said Jeffrey Croteau, managing principal at Prime Buchholz: “These early investments by The John Merck Fund and by other investors sensitive to sustainability helped set the stage for significant growth for asset managers that incorporate ESG into their processes.”

And as they progressed, these firms sparked the interest of some of the largest traditional investment houses. The acquisitions of Imprint Capital by the investment bank Goldman Sachs in 2015 and of Aperio by BlackRock, the world’s biggest asset manager, in 2020, signaled the mainstreaming of sustainable investing in the U.S. market.

Movement building

We also joined like-minded charitable organizations and educational institutions in making the case for sustainable investing, participating in conferences hosted by groups including the National Center for Family Philanthropy, Confluence Philanthropy, and the Salk Institute.

(Creative Commons/Peg Hunter)

In becoming one of the first signatories of the Divest-Invest campaign in 2014, we committed to removing all fossil-fuel holdings from our portfolio and investing up to 10% of our assets in climate solutions. We met the divestment goal a year later, having fully exited holdings in fossil-fuel-industry companies on the Filthy 15 and Carbon Tracker 200 lists. We achieved the second objective by investing in funds targeting climate-protection activities such as clean power and energy efficiency.

Through this combination of private and public commitment, The John Merck Fund and other participating foundations helped the sustainable-investing movement overcome initial skepticism and begin acquiring progressively greater scale and force.

Wallace Global Fund

“The John Merck Fund’s willingness to step forward as part of the first cohort of the Divest-Invest campaign was critically important,” Ellen Dorsey, executive director of the Wallace Global Fund and founder of the campaign, said in 2020. “[Divest-Invest] was fundamentally a peer-to-peer challenge to our sector to be responsible philanthropists. Not only did that first cohort generate the momentum of what we now know was an immensely successful movement in philanthropy, it also put the wind at the back of the activists around the country and the world who have worked successfully to get university endowments [and] religious endowments out of fossil fuels and into climate-change solutions. Together we were also as a sector able to prompt investment firms to create fossil-fuel-free products. So those early adopters really set off a snowball effect.”